Recent Common Misconceptions on the Russo-Ukrainian War

Fuel, tanks and Tomahawks, the media as ever is wrong

December 16 2025

Posted my intention to write about this a few days in this X post.

https://x.com/ZimermanErik/status/1998570938380530091

The mainstream narrative in the West of late has included three often repeated claims, all implying the near collapse of Russia, or at least its capacity to wage war in Ukraine. For those who like to check, verify, learn, analyze and (even!) think, rather than be “educated” by headlines… a deeper look at these three claims.

In this article:

1. Russia’s war machine and war economy are being brought to their knees due to Ukrainian strikes on its oil refineries.

Here we will not explore Russia’s overall economy under the unprecedented sanctions (hope to get a chance to do that at a later point), but only address the claim that these recent oil refinery strikes will collapse the Russian economy.

Such headlines and videos have been everywhere in the last few months.

Here just a small sample from a quick search:

A closer look at some popular examples:

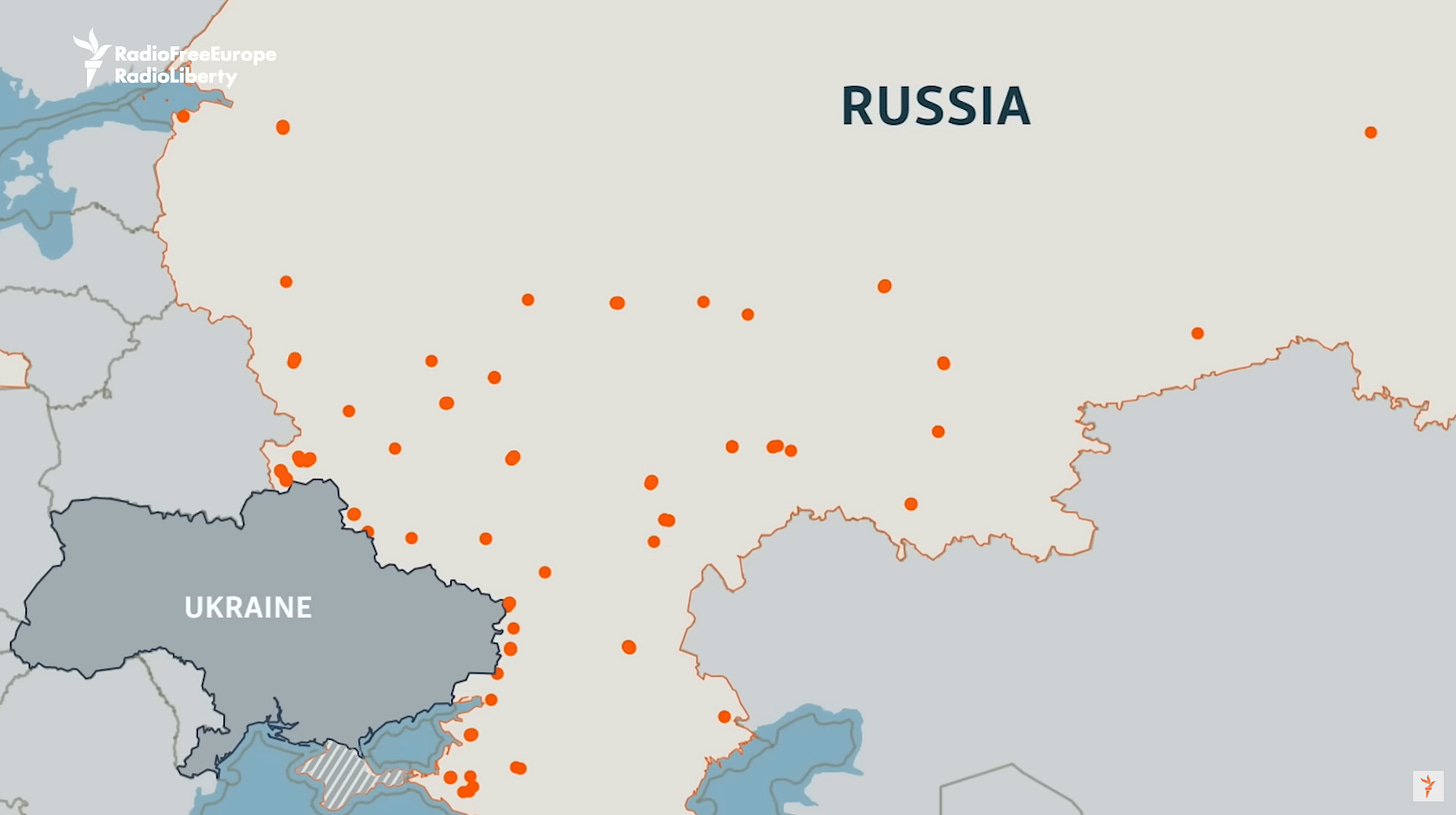

The above recent “Radio Free Europe” video included this (following) map of hit oil refining sites this year; over 100, and it reports half of Russia’s major oil refineries have been attacked (some, dozens of times).

https://euromaidanpress.com/2025/12/07/frontline-report-2025-12-06/

The video goes on to report that 10% of Russia’s oil refining capacity has been taken out.

More dramatically, a recent Euromaidan report, which was quoted very widely, reported over 180 strikes on refineries (and ports), heading towards 200 by year’s end. It claims the refining capacity has been cut by a much more significant 25%, and to indicate the imminent collapse, reported that Russia’s Rosneft’s net income was slashed by 70%.

https://euromaidanpress.com/2025/12/07/frontline-report-2025-12-06/

They provided the following map of major strikes.

Additionally, the Euromaidan report says Russian refining capacity is down to only 5 million barrels per day. These numbers are for the first 9 months of 2025, in a YoY comparison.

So is all this true?

Many of the facts are true (or close enough), but not the implications. First let’s understand why oil refining specifically is being targeted.

Oil refineries are prime targets (I discussed them earlier this year as targets for Israel in the Israel-Iran war). They make for dramatic images and raging fires. Refining capacity tends to be concentrated in large facilities with all too attractive targets; columns, hydrocrackers, desulfurization units, and pipe-racks are vulnerable to small warheads and burn magnificently. A few well-placed hits can idle a plant for weeks if not more.

Fires at refineries, can also range for days until contained. And theoretically, they produce the finished products (such as diesel and jet fuel) that the armed forces and economy actually need. Raw extracted oil (crude) is not directly used by the economy so in this respect, this makes the refineries better targets as well. Finally, many refineries are closer to the markets where their products are needed, and (as the earlier maps show), closer to the front line.

Upstream production on the other hand is very far (from the front line) and dispersed. We are looking at 1,500 to 2,500 km from Ukraine (West Siberia, the Urals), and thousands of wells and gathering lines. Crude terminals are more concentrated but tough targets. Strikes thus far has shown Ukraine can pause operations at some terminals, but Russia has restored loadings rather quickly. Ports and large oil hubs are also heavily defended. Pipelines and terminals are part of a more redundant system, harder to damage, and easier to patch.

For these and other reasons, the refineries were seen as the softer and more worthwhile target for Ukraine. This means that Russia’s overall oil production and transportation networks have remained fairly untouched.

Now, as mentioned previously, it is true that the refined products are the lifeblood of the economy (and armed forces), and so depriving Russia of refined hydrocarbons would be a very significant blow. But the crux of the matter is that such a deprivation has not occurred (other than perhaps due to temporary shocks before market participants adjust) and cannot occur by the method employed by Ukraine (long range drone strikes on Oil Refineries).

We need not look far for an example. Ukraine has long been deprived of its refining capacity by Russian strikes (since early in the war back in 2022). Ukrainian gas stations throughout the country sell to the public largely without issue. Ukraine simply switched to importing all of its refined products (even before the war, Ukraine was a big importer, but it did have significant petrol, LPG and diesel, in that order, production capacity).

Russia of course is a well known vast producer of oil and net exporter of refined end products. The Ukrainian strikes caused a Russian ban on exporting certain type of refined products. Back in the end of September, Russia implemented a full gasoline export ban, and a partial ban on diesel and other fuels/oils (it targets resellers and non-producers only).

The effect of this is that while indeed domestic gasoline production volumes have dropped, Russia’s oil production has not. This has simply triggered a redistribution in the oil network as far sales, imports and exports. Most specifically and importantly, Russia has exported more of its oil (that was not refined domestically) than previously, and imported more gasoline, that was refined elsewhere, to make up the shortfall.

This of course has economic consequences. Russia’s companies processed oil into refined products in part to export in order to profit. This is a value added process, and exporting the crude oil instead, is normally of lesser value. There is obviously an economic cost in having many of your refineries attacked and heavily damaged; but it alone will neither cripple the Russian economy nor deprive it of gasoline and diesel. These products were simply imported in greater volumes than previously from countries such as Belarus and China, which can take Russian oil freely and refine it without worrying about Ukrainian drones (to date that is).

Now that we have laid out that fundamental dynamic, let us consider how much of Russia’s domestic refining has been crippled, and what the implications may be. Let us begin by digging into Rosneft’s released numbers that were so widely reported to glean some understanding from it. The strikes and the release have certainly affected the stock.

The most dramatic part of the headlines refer to the 70% drop in Net Income. We should understand that this refers to a bottom line profit, and is not necessarily correlated with volumes of production nor revenues. Let us dive in and find out.

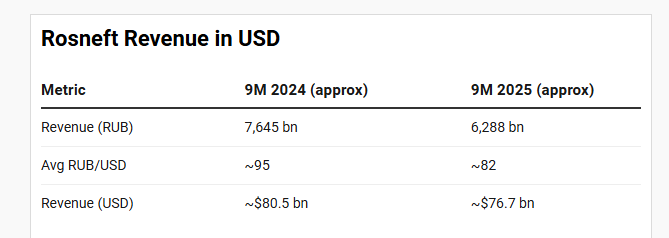

In its release, Rosneft said its revenue dropped by 17.8% in the first nine months of the year to 6.29 trillion rubles (vs 7,645 in the same period of 2024). This is certainly a significant drop, but it is very far from the 70% collapse reported.

The company stated that “The Company’s revenue in 9M 2025 decreased by 17.8% year-on-year, amounting to RUB 6,288 bln, due to declining oil prices and a stronger ruble”.

The company specifically sites the stronger rouble as key in the decline. So while the company received 6.29 trillion rubles vs 7,645 trillion in 2024, their value in dollars is a much smaller decline.

For a back of the envelope calculation, let us estimate the average exchange rate in the 2024 period as 95 RUB to the dollar, and in the corresponding 2025 period as 82 RUB to the dollar.

This relatively small drop in USD corresponds to a 4.7% drop, rather than the 17.8% drop in Roubles, and certainly very far either way from a 70% drop blasted in the headlines.

The second factor the company mentioned is the obvious one, oil prices. Oil prices in 2024 ranged roughly from $75 - $80 per barrel and were only $60 - $67 thus far in 2025. That right there is a 20% decline in oil prices, without any drone strikes in the mix.

Gasoline prices dropped even more sharply, from about $90 - $110 in 2024 to $70 - $90 thus far in 2025.

If oil and gasoline prices were equivalent to that many Less dollars per barrel in 2025 than in 2024, and each dollar would buy you even Less roubles as well, it is not surprising that Rosneft’s revenue would drop by 17.8% in terms of roubles, but rather surprising that it did not drop by more! That is before we consider any drone strikes at all!

Therefore, despite the widely quoted headlines, the Roseneft November 28 Press Release does not indicate a collapse in production volumes, much to the contrary.

This leaves us with explaining the 70% drop in Net Income.

If everything is more or less the same in terms of sales and revenues (given oil prices and currency exchanges), one is left wondering about that massive net income drop. We are not satisfied leaving the matter unexplored of course, nor does it suffice to at this point leap to one conclusion or another either arbitrarily or through prejudice, but rather will dig for the answers. As it turns out, getting a rough idea of what is going on is straightforward enough.

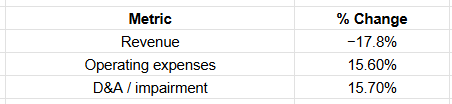

While revenue dropped 17.8%, Operating Expenses increased 110 trillion RUB, about 15.6%, and Depreciation, amortization & impairment (D&A), or as the company reported it “Depreciation, depletion, amortization and impairment”, increased 97 billion RUB (15.6%).

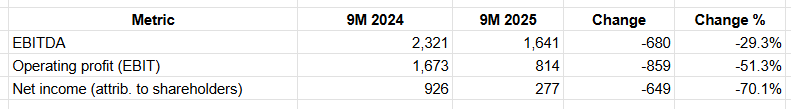

With revenue going down and these two items going up, each just as much, net profit is obviously squeezed. An amplification effect. We thus end up with our 70% Net Income Loss. But it is useful here to notice the difference between EBITDA, EBIT, and Net income:

The revenue drop of 17.8% is mostly explained by lower oil prices and a stronger Ruble. A small part of it is due to volume drops (more on that later). EBITDA is down 29% which is explained by the revenue drop and a 15.6% increase in Operating Expenses. This is likely increased security measures, rerouting, heavier and less efficient logistics, increased maintenance and repair and other factors caused by the increasing drone strikes. As the refineries got hit, the network rerouted and adjusted, and this was not free.

Once we include the impairments and depreciation, that is our YoY EBIT change, we get to the a 51.3% drop (a drop of 859 billion RUB). Over half of that difference is in the additional 97 billion RUB of increased DA in the press release, and then we are still missing another 82 billion (859 billion - 680 billion = 179 billion) that appear to be missing. In other words, the difference between EBIT and EBITDA should only be the “DA”. So where is the rest?

Well, the press release as is often the case is showing an Adjusted-EBITDA. First let use a table without adjustments as we would get from the full release, that is IFRS-consistent.

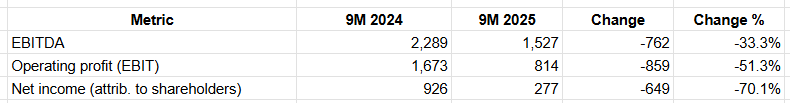

The only thing that changes is the 9M 2025 number for EBITDA from 1,641 to 1,527 billion RUB (and the 9M 2024 number slightly as well). Then our initial drop is of 33.3% rather than only 29.3%. I will address why this is further evidence to our conclusion, but first let us continue.

So, after considering a 33.3% drop in EBITDA, we move on to see a 51.5% drop in EBIT. That difference is made up precisely by the 97 billion RUB in DA. In the adjusted EBITDA number in the press release, the company was also deducting expenses outside the strict “DA” expenses that it considered “DA-like”. These additional 82 billion RUB are a large part of the Operating expenses (OPEX) increase of 105 billion RUB.

The fact that about 80% of the increase in those expenses could be seen by the company as “DA-like”, is further indication that they were damage-related, or at least “disruption-related”. Emergency repairs, logistic inefficiencies, one-time operational disruptions, inventory write-downs, are all likely examples. They were not strictly depreciation or impairments, to be placed within the DA, but similar enough (and management hopes “one-time enough”), to be included in the expenses deducted (not counted) from the Adjusted EBITDA.

An additional clue is that even while EBITDA is dropping over 30%, and strict DA increasing 16%, CAPEX increased 6.3%. That is consistent with hardening and/or rebuilding. In a normal oil-cycle downturn, companies tend to cut or defer CAPEX. You would expect a 10 to 30 percent cut in CAPEX when EBITDA is down over 30%, especially since that previous 9M 2024 period itself had a large 15.7% increase in CAPEX.

Most of the CAPEX is being spent in Upstream development as the company has been reporting, but infrastructure hardening, repair and replacement of damaged assets has been part of the equation. Due to accounting practices, normally such CAPEX increases would not offset impairments and write-downs until the work was more advanced or completed and capitalized. Impairments are recognized when the damage occurs. CAPEX is capitalized when the rebuilding takes place. So you can have both be increasing in the same year.

In other words, the statements support a picture where:

OPEX is increasing (immediate expenses):

Emergency Repairs

Security Costs

Temporary Fixes

Disruptions

Rerouting & Increased logistic costs

Inventory write-downs

DA is increasing as asset values are reduced:

Damaged facilities & Equipment

Derated Refineries

Shortened useful lives

CAPEX is increasing:

Equipment Replacement

Reinforced infrastructure

New routing infrastructure

Security and Hardening-related capital works

All happening at the same time.

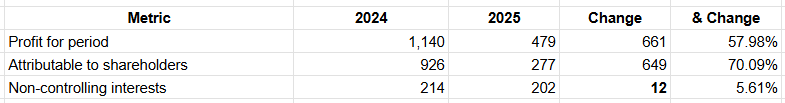

OK, so we are at a 51.3% drop Year-over-Year. How do we get to the reported bottom line drop of 70%.

Basically what remains to get us there are taxes and non-controlling (minority) interests. Taxes dropped by 174 billion RUB:

9M 2024: 379 billion RUB

9M 2025: 205 billion RUB

Lower prices (and lower still in RUB) means less revenue, less profit and less taxes; but not proportionally and not linearly. This happens for many reasons including that the oil industry includes many taxes not directly on profit. Extraction fees for example are standard. The state receives its share for natural resources extracted from the ground.

2024: 379 / 1,519 = 24.9% effective tax rate

2025: 205 / 684 = 30.0% effective tax rate

The effective tax rate increases by about 5 percent.

Looking at PBT (profit before taxes) and taxes increases the YoY drop to 58%. Significantly over 51% but still not at the reported 70% drop in income.

We get to the final amplifier in terms of the year over year percent change. Non-controlling (minority) interests. They get a share of profit (and/or fixed claim) before shareholder profits can be distributed.

As we can see, the NCI barely dropped, 12 billion RUB YoY, a mere 5.61% when overall profitability was 58% lower. These minority interests behave somewhat more like fixed claims when profits drop. They may include entities such as regional JVs, refining & upstream partnership, subsidiaries with fixed minority claims, and other JVs which allocate profits before parent-level consolidation. They may also include other state-linked entities or partnerships. That (the NCI payment) is the final amplifier and it leaves the shareholders with the total 70.1% drop in shareholder Net Income.

In summary, we are seeing that lower world oil prices, and a more expensive Ruble, decreased revenues (in Rubles). Strikes did not significantly decrease output volumes, but did change operations. The company adapted the network. While overall volumes were not very different, the type of products that were made and to whom they were sold did in fact change. This, together with increased anti-drone & security measures plus repairs and infrastructure hardening, significantly increased costs and impairments (which may or may not be “real” to a large extent). The outcome was a large net income drop, but in no way did it translate to an equal production drop.

The company’s release includes language that points to our conclusions. In terms of strikes (ie “security measures”), the high RUB price (ie “key interest rate”), and the fact that the company considered many of these expenses “non-monetary” (ie impairments) and “one-off factors” (ie the expenses not in DA that were still excluded in the Adjusted EBITDA by virtue of being “DA-like”).

…increased costs of anti-terrorism security measures, high level of the Bank of Russia’s key rate, and the strengthening of the ruble since the beginning of the year put additional pressure on the Company’s performance for 9M 2025…

The high level of the Bank of Russia’s key interest rate continues to have a significant negative impact on the profit. In addition, non-monetary and one-off factors adversely affected the indicator’s dynamics during the reporting period.

Now let us take a look at production volumes to verify the theory.

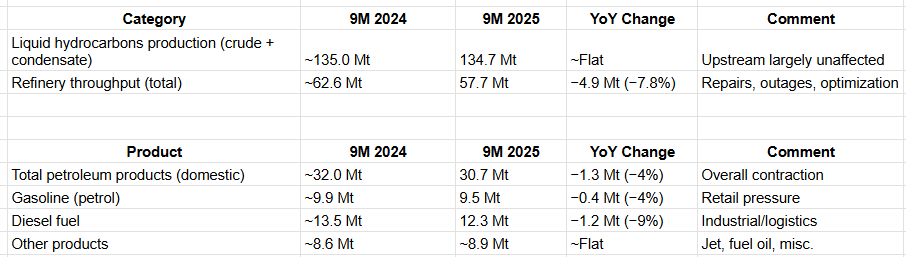

Indeed, total production volumes (upstream production) was flat and unaffected. The Refinery production, as would be expected, experienced a significant drop of 7.8%, but nowhere near catastrophic. When we look at the additional breakdowns, we see that Diesel fuel volumes took the largest hit, with a 9% reduction. Gasoline had a smaller drop of 4%, and “Other” (which includes jet fuel), actually increased. As diesel production is a more serialized process (starting with and dependent on tall high pressure DHT / ULSD units) whereas gasoline has more parallel processes available (blending options etc), it is not surprising that diesel production was harder hit.

We postulated that since oil production upstream was not affected, the refining shortfall would simply be imported while more oil could simply be exported. We also discussed how certain established routes and contracts could be disrupted so sales would shift to the spot and international markets.

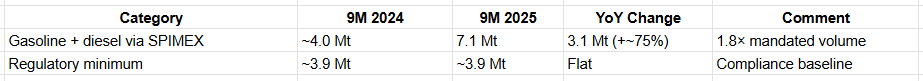

We can see evidence for this fact by looking at the SPIMEX (Market Exchange) Sales:

SPIMEX sales for gasoline and diesel were up a whopping 75%, which was 1.8 times the mandated volumes. Russia mandates certain minimum volumes of refined products that must be sold on SPIMEX in order to encourage the growth of that market and provide it with enough inventory and liquidity. Apparently, the oil companies prefer fixed contracts, which tends to command higher average prices. Here, ROSNEFT went far above the minimum, nearly doubling it. In the same period in 2024 as we can see, the company just barely met the minimum requirement.

As certain refineries went off line and could not supply their traditional customers, other refineries further east (or facilities with imported fuel) could supply the SPIMEX market extra amounts, not having the established regional customers who could take the volume. Independent market players, could take the capacity and pay for the logistics to transport it to where they could use, blend, store or sell it.

Rosneft is highly integrated, from crude to refining capacity to depots, wholesale and export. If this vertical coordination is disrupted and under stress due to strike damage, repairs and security upgrades, outages and bottlenecks can result. Sales on SIMPEX is the easy outlet for that disrupted supply chain. It shifts logistics to the buyer, and plenty of different contracts exist. SIMPEX contracts exist by the hundreds and vary not only by product and grade, but also delivery point. There are dozens if not hundreds of delivery points typically used in the market. A few examples:

Moscow region depots

Volga region depots

Ural terminals

Siberian terminals

Far East ports

Specific refinery racks (e.g., Ryazan, Tuapse, Angarsk)

Once you put product available on the market, individual traders may be buy and hedge for any number of reasons. Export bans for example, can encourage traders to buy and store, waiting for their window to export at a profit.

The Rosneft statements gives us a picture of a resilient network adapting, not collapsing. Yes profit for the individual company, specifically for the shareholders at the end of the waterfall did collapse dramatically, but much of that reduced profit is either in one-time improvements that reduce the threat for further strikes, or in the form of non-cash accounting entities. Just like assets were impaired and written down, some may be capitalized later on. Russia’s oil & fuel infrastructure is not collapsing, but rather paid for its increased security, resilience & immunity from further strikes.

Finally, in the long term the company will enjoy some form of insurance relief on much of the damage. This will take time, and negotiations but some form of assistance will come from the state in this regard (though this is still a loss for Russia as a whole, even if not for the specific company).

So is Russia’s oil infrastructure collapsing due to Ukrainian drone strikes? No. Overall production is untouched, and the network will simply adapt, though not without cost.

Refineries make the most appealing targets, as they are a soft target bottleneck, but for similar reasons even in the worse of refining capacity declines, the gap can simply be made up by importing the refined products, while the fact that overall crude production is untouched allows for its export. Economic cost, yes, but the end of gasoline and diesel supply, no.

It is important to note that there are scenarios where destroying the refining capacity of a country can be devastating. It typically requires some of the following factors to be at play:

Highly concentrated refining bottlenecks. Not hundreds of refineries but a few key sites.

Highly concentrated import / export routes. A few (or less) reachable gateways; port terminals, pipelines, railways.

Highly subsidized domestic consumption of refined products.

If you can’t completely block off a country from international trade (and thus diesel & gasoline imports), then the last item on the list is crucial in terms of having a real catastrophic economic impact. For example, in Iran’s case, a single refinancing facility at Setareh Khalij Fars provides ~45% of the total domestic gasoline supply (additionally, ~15% of total refining output). Pre-12-day-war (with Israel) Iran was in terrible economic shape (much worse now). There is little money, productivity, or even water. The one thing Iranian citizens were used to is very cheap gasoline, as the government heavily subsidizes domestic gasoline consumption. What exists of the Iranian economy is highly dependent on this sub-market price source of energy. You are talking about customers often paying a tenth or less of real market prices for a liter of gasoline. And that is about the only benefit they can expect from their government and what helps them offset rampant inflation (which is caused by the massive government spending, which includes the massive fuel subsidies). If you take out that single refinery, the fragile Iranian economy would collapse, because it is as is very fragile and highly dependent on the heavily subsidized fuel.

Russia on the other hand, does not subsidize domestic consumption of gasoline and so importing it rather than producing it for some time does not have a catastrophic economic effect for the state as a whole.

Looking beyond refineries, as we saw earlier Russia’s production is too far east and too spread out for Ukraine to significantly hurt by long range strikes. The next best bottleneck would be export infrastructure. Major pipelines, oil terminals in ports, railway oil depots; difficult for Ukraine to really dent but possible. The only place where large volumes of oil are really unprotected and vulnerable is onboard oil tankers, sanctioned (“shadow fleet”) or not. We already are seeing early signs that a desperate Ukraine, noticing that neither sanctions nor its refinery bombing campaign are having the desired effect (odd since as I mentioned, Ukraine had its refining capacity blown to bits early in the war without causing any major issue) may increasingly try to attack Russian oil tankers on the high seas.

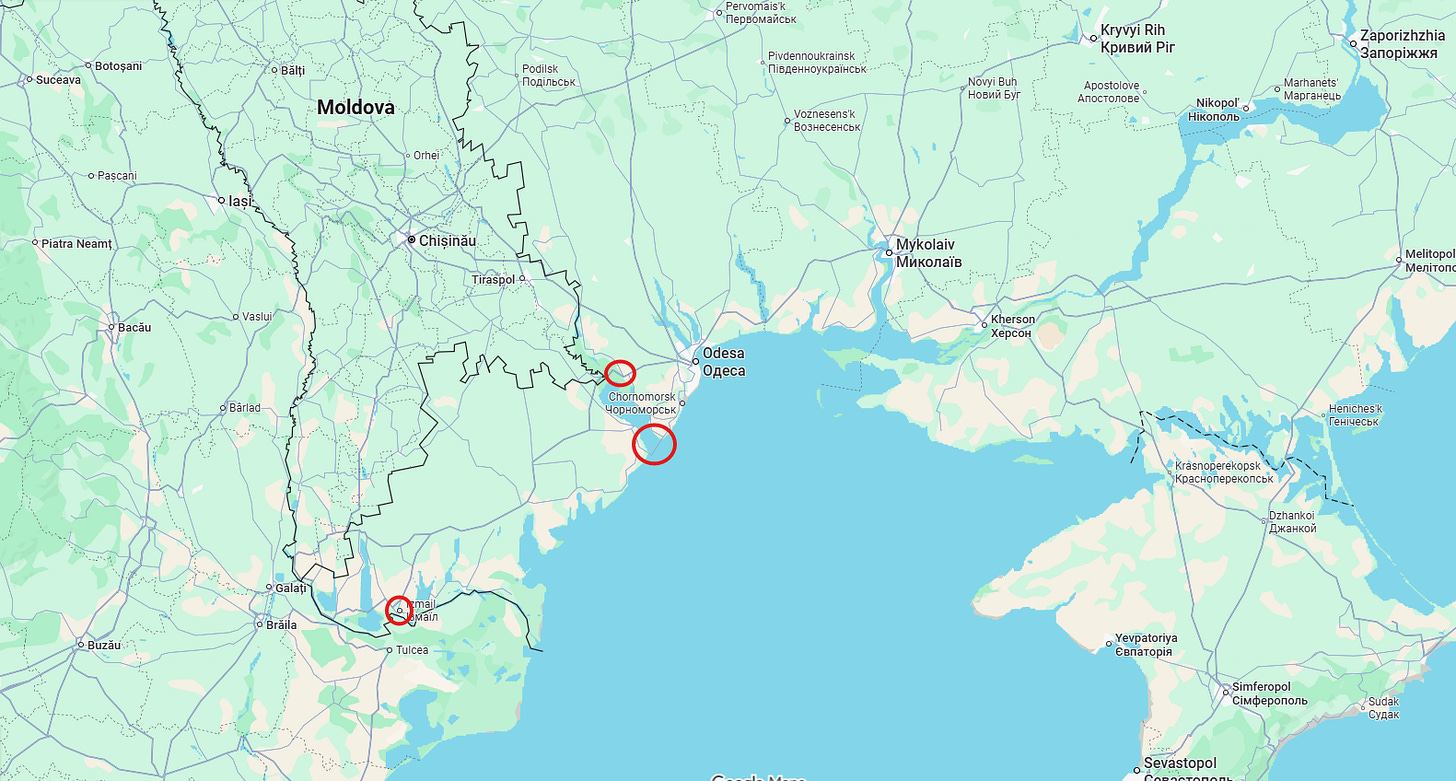

I will leave discussion on that subject for a later piece, as it is rather interesting. I will just point out that Ukrainian imports of gasoline and diesel mostly come from the Danube river ports from Romania. That is a partial logistic bottleneck that can also be targeted by Russia in retaliation. The river ports, terminals and highway/railway bridges over the Black Sea and the Dnister River are key chokepoints.

Routes through Moldova are not developed and are partially blocked by (Russian ally) Transnistria. Russia could significantly reduce Ukrainian fuel imports from this corridor, making Ukraine have to rely only on the more expensive and logistically prohibitive Polish alternative. The Polish Ukrainian border is plagued with heavily congested crossings with long queues as it is, not to mention political tension. The Romanian refineries on the other hand, are export oriented and have access to marine Black Sea crude.

Thus, indeed despite all the sensationalist headlines, Ukraine’s massive investment in long range strikes against Russian refineries, at least in the short and medium term (anything can happen long term), is not likely to lead to any significant results; the Russian network will gradually continue to adapt, without losing much of its refining capacity while it moves further east, air-defense improves and local facilities upgrade and harden (nets, cages/heavy mesh, fortifications, earth berms, dummy pipes & structures, close area anti-air defenses, moving underground) against potential strikes.

2. Russia is out of tanks & other armored vehicles (hence resorted to infantry attacks).

This one is particularly funny because many of the same folks also claim that tanks and armored vehicles are now obsolete (so who cares if you are all out?). On this second question, I am pleased to say that @DelwinStrategy on X (Substack is Delwin - Military Theorist) let me know he beat me to the punch on this, and he did a great job on this important question:

He provides the article on substack as well.

In general, the issue is tackled very well and thoroughly in this report and the conclusion reached is broadly correct. I can only highlight and add that most folks are confusing the disappearance of long idle (and decaying) armored vehicles in huge known storage bases in Russia, and their disappearance from Russia.

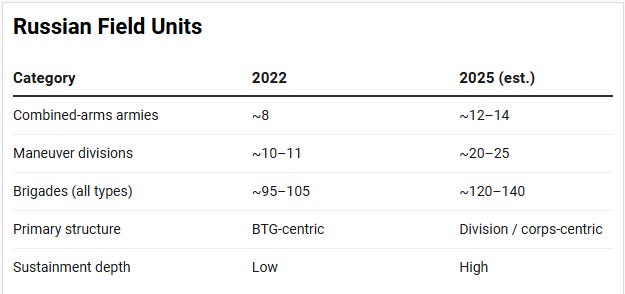

Quite on the contrary, a tank previously rotting away in a long term storage site for decades disappearing from the site does not signify a destroyed tank by Ukraine and thus its deletion from the order of battle, but rather the Re-Activation of the tank into the Russian armed forces. Tanks were refurbished and re-activated in massive volumes. We have to keep in mind that the Russian armed forces grew massively since 2022.

Divisions have more than doubled. The reason brigades have grown by a lesser factor is because it is not an apples-to-apples comparison. Prior to the war, brigades were really BTGs (if that), which are hollowed out brigades, really just reinforced battalions. Today’s Russian brigades are closer to full fledged brigades. As an example, 10 to 14 additional divisions would alone require anywhere from 1,800 (10 per division) to 3,100 (14 per division) tanks. Restrengthening existing understrength and BTG-style stripped brigades would also entail anywhere from 400 to 1,200 tanks. When we add other brigades and reserves, the unit growth alone would require anywhere from 2,500 to 5,100 tanks (very rough approximations for illustrative purposes).

Estimates for the main battle tanks removed from storage range from 4,000 to 6,000 (Delwin’s “Reactivated” number stands at 4,083), which is very much in line with what would be needed only for the army’s growth, plus some replacement losses. Armor is needed not only for each unit, but for training of new (and existing) units. All units, training, fighting and otherwise require levels of reserves and replacements as well.

Russia turned its long depreciating assets (economic output of the Soviet era and through the 90s), into useful battle stocks1. It re-armed and grew its army, not ran out of armour.

To do this, it massively expanded its reactivation, repair and refurbishing capacity. Since Russia is generally advancing in the war, while Ukraine gives territory, many abandoned and damaged armored vehicles (from both sides), are eventually recovered by Russia. The difficult battlespace and kill zones rarely allow either side to retrieve damaged or abandoned vehicles while they are near the front line or grey zones. As Russian forces slowly advance, eventually logistic units are able to salvage many of these vehicles. Anti-drone additions such as cages and porcupine armour also reduce the actual damage sustained by the vehicles themselves and assist in refurbishing.

As the deep reservoir of old Russian armour is exhausted, Russia’s refurbishing capacity can be transitioned to production capacity. Production capacity has exploded since the start of the war, and that is despite the fact that the powerful incentives to prefer refurbishing capacity. Refurbishing and even updating an old tank is drastically faster and cheaper than producing a new modern one. As such vast refurbishing capacity continues to become less needed, much of its potential is transferred to additional new production capacity.

And it is regarding new production that I can comment on Delwin’s report. He (knowingly I believe) used very conservative new production numbers, and he himself reminds us:

This [New Production] remains the most uncertain variable, as publicly available OSINT data is limited

For simplicity, to look again at main battle tanks only, he estimates 2022 T-90 production at 40 per year and doubles it to 80 for the 2025 estimate. Indeed the pre-war number is likely to be within the ballpark range. The 2025 number however is likely to be significantly underestimated.

Actual numbers are highly debated, and there are both Russian-sourced claims and Western estimates to look at. One useful indicator is trying to figure out the proportions of modern models such as the T-90M seen in the battlefield compared to earlier in the war (when they were mostly absent). It is not perfect of course, especially since tanks are rarely seen in action today and so it would be easy to “cherry-pick” the best tanks when in fact they are to be used.

We are not going to get bogged down in these calculations but will be satisfied in quoting a few sources who attempted this:

Defense Express reports that the world famous Janes estimates T90M production at 250 per year in late 2025, up from 50 per year pre-war (very close to Delwin’s 40).

With a lot more detail, and using different (but ultimately supporting) methodology. Front Intelligence estimates 240 T-190 production already in 2024 (though importantly including new production, capital overhauls and modernization), and being sustained in 2025. Since pre-war production had little economic incentives to cover more than export sales, it is quite reasonable to understand today’s Russian war economy is producing weapons at vastly different scales.

Indeed Russia is still far from running out of armor of all types, and since lately less armor has been used and lost, it is likely that its reserves are actually growing and being modernized. The average tank being used in early 2026 is likely to be far newer than the average tank used in early 2023 as reactivations and growth were in full swing.

We can also expect that new models, and/or upgrade kits, with drones specifically in mind, are being developed. Has all this been easy for Russia? No, not at all… but it is not easy Russia is looking for, but victory.

3. Tomahawk missiles will be (or would be) the game changer!

This third claim is of a frequently repeating type... the next “wunderwaffe” is alone the key to victory; going back to my favorite and original wonder weapon claim back in 2022.

Since then, we have discussed the phenomena many times as the mainstream western media told us each time that if Ukraine only get this or that weapon from the US, it would quickly dispatch the Russian bear.

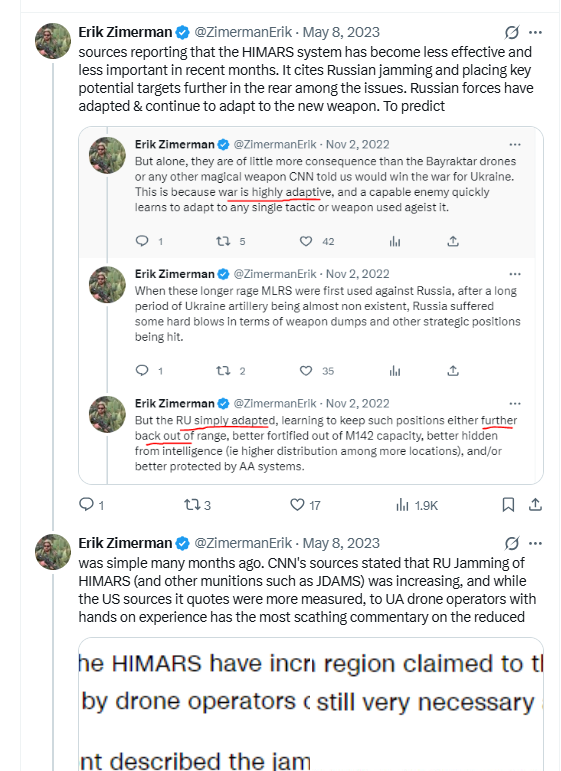

Specifically, we discussed the HIMARS systems in detail, which common reporting had as certainly turning the tide. Nearly a year after our discussion, western media started to admit the HIMAR’s effect had been overhyped;

and included this piece:

So, the NLAW, Bayraktar, the HIMARS ATACMS, the Leopard 2 main battle tank, and more recently the F-16 were all game changers that came and went. Now, with only slightly diminished enthusiasm we have been told that all which holds back a Ukrainian victory is the (absence of) US Tomahawk missile.

This claim does not need much analysis to debunk. In fact, back in our 2022 analysis of the similar situation regarding HIMARS systems, the key aspect remains the same:

…is of no doubt that having the HIMARS is helpful to Ukraine, especially if it has enough high quality ammunition and the supply lines to get it to launchers, it certainly beats not having any long range artillery, but being able to strike positions behind the front line alone does not victory ensure, because if so Russia would have ended this war long ago. Even more ironically, Ukraine had much of these capabilities as well, being an army that heavily relied on MRLS systems, like Russia.

Russia has a vast arsenal and ongoing production capacity of weapons with similar capabilities to Tomahawk missiles. It also uses them in large volumes (which Ukraine would not be able to duplicate with Tomahawks, as the quantities delivered by the US would be limited) against Ukraine. This alone, in no way quickly crumbles the Ukrainian armed forces or its capacity to keep on fighting. Admittedly, the effects on its economic and industrial capacity are less critical than in the case with Russia, because Ukrainian weapons and treasure to continue the fighting are created outside the country by its backers (a luxury Russia does not share).

However, Russia’s massive and frequent aerial attacks (by cruise, ballistic and hypersonic missiles as well as massive waves of long range drones) have not even been able to stop Ukrainian domestic production of weapons, such as short range and long range drones and missiles, from growing significantly (let alone destroying it). From long range ballistic missiles such as the Iskander, the quasi-ballistic hypersonic Kinzhal, to cruise missiles such as the Iskander-K, Kalibr, and Kh family (such as the Kh-101 and Kh-102), and huge volumes of long range drones, Russia has and utilizes one of the largest (if not the largest) arsenals of long range munitions (cruise missile & otherwise) ever seen. Yet the war continues…

Simply put, the Tomahawk missile, though certainly an impressive, mature and tried cruise missile, does not bring any capability to the Ukrainian armed forces that they already do not have.

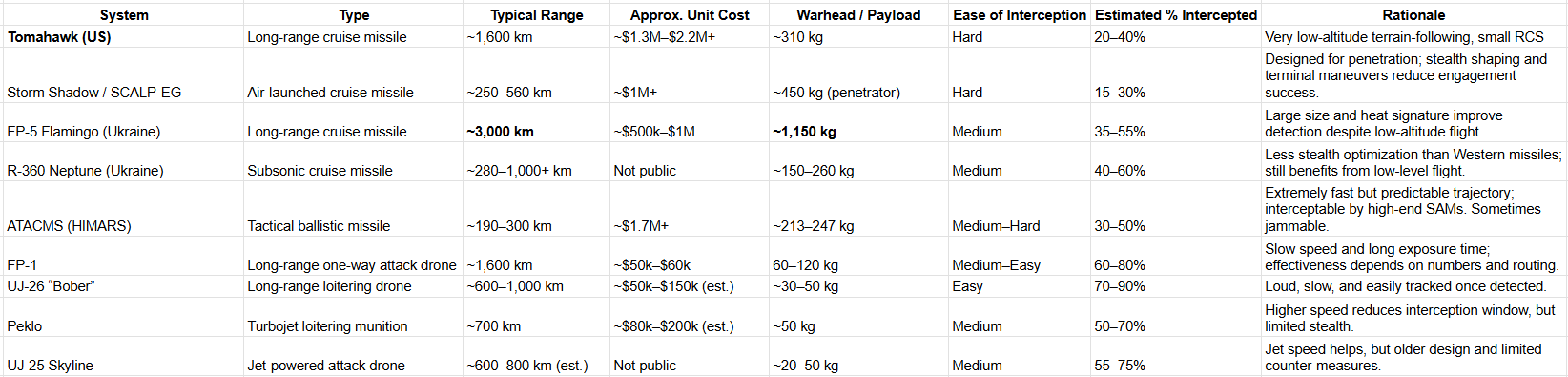

Let’s take a look.

This table is meant only to get a very rough idea of the situation. Every one of those parameters can be researched and debated at length. I only quote here what is easily available and reported. Much of the information is classified so these are ranges and estimates. What we can easily see however is that the Tomahawk is a long range cruise missile, that is highly accurate, expensive and difficult to intercept.

Ukraine already possesses and routinely uses weapons with similar and sometimes superior capabilities that are also less expensive and available in higher numbers.

For example, while the Tomahawk’s main attraction is its 1,600 km range (in order to reach deeper into Russia), its payload is relatively small, about 310 kgs. It certainly cannot take on hardened or dug in targets. It also, can be intercepted, and increasingly so as any AA system learns and adapts to the new weapon.

Ukraine’ domestically produced Flamingo, is a cruise missile that has ranges of nearly double the Tomahawk and a much larger payload at over one ton. It is likely less accurate and easier to intercept, but would be available in greater numbers and is cheaper than a Tomahawk. In the previous section on refinery strikes, we see that Ukraine, without Tomahawks, has successfully struck refineries and other facilities deep within Russia2.

Ukraine’s growing arsenal of long range drones are an order of magnitude less expensive, available in much larger quantities and have equally long ranges; such as the FP-1 at 1,600 kms as well.

You can get up to 36 FP-1s for the cost of one Tomahawk cruise missile. Even if only 10% get through, that would still be 3.6 strikes for every one Tomahawk launched, which is not the same as every Tomahawk hitting its target. Even at a 70% success rate (which is exceedingly generous), leaves us at ratio of 3.6 drone strikes to .7 of a Tomahawk strike (or 36 to 7). Even considering payload, the FP-1 doubles efficiency since it carries about half the payload of the Tomahawk. Additionally, 36 cheap drones, require at the very least 36 anti-air munitions to intercept (often much more), and typically many more than one Tomahawk missile would. Thus the drones exact additional costs on the enemy and further help exhaust his air defense systems.

Of course when you consider the benefits of different weapon systems working in tandem, including long range drones, Ukraine’s Flamingoes and European high quality cruise missiles such as the Storm Shadow ATACMS for somewhat shorter (but still long) ranges, as well as the optimization of air attack tactics needed to confuse/overwhelm the enemy’s air defense layers, the Tomahawk capability is far from a game changer or magic bullet missing in Ukraine’s arsenal.

Is there any advantage to it at all? If this is so, why does Ukraine want them so badly?

For two main reasons. Firstly as always it is money. It is not that the Tomahawk missile’s capabilities would somehow be the secret for victory, it is just that a missile is a missile. And 1 or 2 million dollars (a Tomahawk’s cost) is 1 or 2 million dollars. Ukraine does not need the Tomahawk specifically, it needs lots and lots of weapons that cost lots and lots of money. Getting Tomahawks from the US is simply another way to get more money. They would be happy in this regard to get cash and produce Flamingos themselves instead (for one, more graft to go around!). The Tomahawk commitment is likely to come as a net total increase in US support.

In this regard, what is more important than getting Tomahawks, is the number of them! And in this regard the number the US would provide (as well as the systems, infrastructure and teams to launch them (who would themselves become targets)), would be far too little to make a significant and strategic difference in the war. Theoretically, very large numbers of tomahawks and the capacity to launch them, would indeed have a very big impact on Russia’s ability to wage war, its economy and industrial base… but these are not the numbers that we are likely speaking about.

Secondly and more importantly I believe, Ukraine desperately wants the US Tomahawk supply because it signals an additional and increasing US commitment. It keeps the US as an active and increasingly aggressive ally. It further invests the US in Ukraine’s success (and how successful its weapons are perceived to be). Ultimately, as an additional escalation, it puts Russia and the US one step closer to direct conflict which has always been Ukraine’s only strategy (to get the West and Russia in a direct conflict), and simply hold on and buy time until this happens (we have discussed that aspect of this war since its earliest days). It has rarely if ever had a realistic plan to actually win on its own.

So Ukraine’s desire for Tomahawk missiles go far beyond the missile’s particular capabilities, which contrary to what we are told by the famously incorrect mainstream media, are no magic bullet in the quest for Russia’s defeat.

The US, for its part, is now finally aware of these dynamics (unlike previously and with previous “wonder weapon” requests), and is reluctant to make another one of its weapon systems and the scale at which it can provide them, seem impotent against Russia (not to mention provide Russia with the opportunity to learn to defeat it). It also is aware of the reasons behind Ukraine’s demands, and is weary to oblige. We shall see.

Let me know your thoughts on these three commonly held fallacies and any others you are interested in.

Depreciating in one obvious respect, while being inflation-resistant in another. Parts, components, hulls, and even copper and steel are ever more expensive in fiat currencies (RUB included), than in years and decades past.

Ukraine has struck targets as deep into Russia as 4,300 kilometers from Ukraine. These however were SBU operations initiated within Russia. Ukrainian drones have been known to hit Izhevsk, roughly 1,300 km from Ukraine and western reports, such as this Bloomberg one, frequently claim strikes 2,000 km+ deep into Russia.

Tomahawk missiles were never feasible anyways by simply exploring a very basic concept... how is Ukraine supposed to launch them? Traditionally the only launchers have been on US Navy vessels, and the US Army has just started receiving the first batch of land based launchers.

Agree with your assessment in the three categories. Especially noteworthy is your emphasis on window dressing in regards to Ukraine’s various procurements, thanks for posting