The Grain Deal is Over

The Battle for the Black Sea Begins

Recently we provided a roughly accurate subtitled interview with President Putin (which was all but ignored in mainstream reporting). It was a very telling interview for several reasons, and we discussed it here:

In this article, I estimated that Putin had finally had enough of being pushed around regarding the Grain Deal.

It seemed very likely to me, despite the common wisdom to the contrary (including statements to that effect from Erdogan himself), that Russia would no longer extend the Black Sea Grain Initiative (outside of the western powers proving a real commitment to honor their thus far broken guarantees). This is in fact what has occurred as we now know. The second part of that prediction was regarding Erdogan and Turkey. Many believed that Turkey’s leverage all but ensured Russia’s continuation of the Grain Deal, and that if even if Russia somehow did opt out of extending the deal, Turkey would simply unilaterally extend it.

This was another false conclusion by mainstream reporting, including some expert analysts, and what we will discuss today. From our earliest discussions on the Grain Deal, including this article:

we discussed how not only was the Grain Deal against Russian interests, lengthening the war (or at least lengthening Ukrainian resistance in the war), attempting to appease the unappeasable, exchanging a great deal for nothing other than further disdain (from a Russian perspective), and most importantly a deal that Russia could opt out of in realistic terms. This final point being critical; we argued that neither Turkey alone nor the NATO countries, were likely to try to break a Russian blockade of Ukraine, especially of its main ports around Odessa.

In recent weeks, we saw a slew of reporting, some based on actual official Turkish (and Ukrainian) statements, and some based on rumors (though widely reported in the Turkish press & elsewhere), that Turkey would escort Grain ships to and from Odessa, even if Russia no longer extended the deal. Let us take a look at some of this reporting:

Above reports from Turkish media (quoted in TASS). Many of these speculations began with official statements from Turkey last October during the previous round of extension negotiations:

and:

In fact, the consensus at the end of the last extension (and that is among more intelligent analysts, not the mainstream reporting one might see on MSNBC which would be unaware of the entire nuanced situation), was that Russia did not have the power to end the grain deal, nor blockade Odessa, and that Turkey and Ukraine had simply called Russia’s bluff.

Erdogan’s 180 degree flip.

After this, we saw what appeared to be a real “flip” by Turkey (perhaps beginning to believe its (and the rest of NATO’s) own hype about Russian weakness). So far straddling the thin line between Ukraine and Russia (for example, selling some weapons to Ukraine, (in)famously the Bayraktar (the classic post on the matter), but honoring (or interpreting) the 1936 Montreux Convention to not allow any foreign non-Black Sea warships into the Black Sea while the conflict goes on and allowing free maritime commerce including to and from Russia to continue. Likewise, Turkey has not officially participated in the sanctions regime against Russia.

Furthermore, using its leverage in the Black Sea as the de facto power over the Bosporus strait, and its apparent neutrality, Turkey has been an important negotiator and arbitrator between both warring parties. The surrender of the Azov garrison in Mariupol, the grain deal, and even general peace talks have been negotiated with Turkey as an important party.

As we discussed earlier, it appeared that Russia in part delayed cancelling of the grain deal, until after Erdogan’s critical elections. Erdogan gained prestige through the deal, and likewise would lose it if Russia cancelled it despite his objections. The leading opposition candidate, appeared to have a much more NATO and Western friendly attitude, and so Erdogan successfully convinced Russia that it behooved her to help keep him at the helm.

Interestingly, almost as soon as Erdogan was secure in his new term, he seemed to execute quite a flip regarding Russia and Ukraine, and all of a sudden.

In short order, Erdogan seemed to flip on Swedish NATO membership, returned the Mariupol Azov leadership to Ukraine (against the agreement reached between Russia and Ukraine), and then started throwing its weight around regarding the grain deal.

With this as background, many were certain that Russia had no choice but to extend the grain deal, or be seen as impotent as Turkey would muscle the ships through..

Even intelligent analysts like reported that the Turkish escort was a foregone conclusion.

We knew better.

First let us analyze the feasibility of the Turkish Navy escorting grain ships to and from Ukraine in the face of Russian blockade. We had Newsweek reporting (quoting “geopolitical strategist” Alp Sevimlisoy) that the Turkish armed forces have the “ultimate supreme power in the Black Sea AND Eastern Mediterranean”.

In fact we were told that the “Turkish Armed Forces possess a level of military prowess above and beyond the Russian Federation”. The Kremlin would not disrupt grain shipments “in any way” again, “as they would face the full wrath” of the military high command of Turkey.

With the mainstream and more in depth reporting clear to us, let us take a look for ourselves.

Comparing the Powers

Such superficial analysis comes mostly from simply comparing the size of the Turkish Navy vs that of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

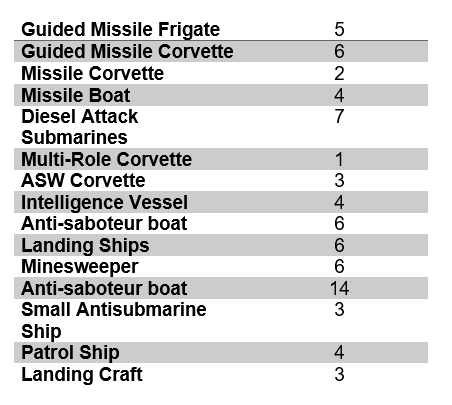

Key in terms of combat power would be the missile boats of all types, the attack submarines, and the anti-submarine vessels. Another way to summarize the fleet would be to note that while it has 5 Frigates and 6 Corvettes, the fleet can be approximately broken down as follows:

Submarines: 7

Missile Boats (of all types): 17

Anti-Submarine vessels: 6

Patrol Boats/Ships: 4

Landing Craft: 9

Minesweepers: 11

Anti-Saboteur vessels: 14

The Black Sea Fleet additionally has Marine Divisions, and 3 Naval Air Aviation Divisions but we can leave that aside for now because the Russian Air Force is very large and would be available and very relevant for this theatre, more on that later.

Compared to this, we can break down the Turkish Navy roughly as follows:

Frigates: 16 (quite old. 8 are Guided Missile Frigates, Gabya class avg circa 2000)

Corvettes: 10 (All Coastal Defense anti-submarine. 5 are older circa 2001 Burak lass and 5 Ada Class relatively modern).

Submarines: 12 (of which 6 are very old)

Minesweepers: 11

Missile Boats/Crafts: 18 (7 very old, 70’s-80’s, 5 are late 90’s and 6 are 2005-2010).

Patrol boats/ships: 21

Helicopter Carrier: 1

Amphibious Assault or Landing Ship: 5

Older and smaller Landing Craft: 30-40

Of course for both navies these numbers are approximate and arguable. Both were attempting to undergo modernization at the outset of the war, and both suffer from certain performance and equipment issues. Russia has also suffered some known and unknown losses, while also added a few advanced ships to the fleet during the war.

We will not do a deep dive on these for comparison but it should suffice to take a cursory look. Even if we compare these (misleading as we shall soon se) arsenals, we should see that the Black Sea Fleet counts on 13 missile frigates or corvettes and 17 total missile boats, plus another multi-purpose corvette. Most of these are relatively modern, compared to the Turkish Navy’s 16 large missile boats (most quite old), plus another 18 (again most very old) smaller missile boats.

The Black Sea Fleet actually easily bests the Turkish Navy in attack submarines, with 7 modern attack submarines vs the 12 mostly outdated Turkish mixed submarine fleet.

Turkey’s anti-submarine ships are limited to 10 costal defense corvettes, half somewhat older and half relatively modern. They barely best Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in this regard which counts on 3 ASW Corvettes and 3 smaller Grisha-III antisubmarine ships. Additionally, Russia has approximately 14 smaller modern ships it terms “Anti-saboteur” boats. These fast Raptor and Grachonok class boats add value to a wartime fleet with their electronic warfare systems and additional anti-air screening ability (besides their modest attack firepower).

Finally, the Black Sea Fleet possesses 4 dedicated Intelligence Vessels, one of which is a modern Yury Ivanov class (2018), which we have already seen fend off Ukrainian naval drone attacks during the conflict. These possess advanced radars, optics, jamming electronics and anti-air capabilities. Turkey has no equivalents.

Thus comparing the Black Sea Fleet to the Turkish Navy, we would conclude that it would be a fight that is up for grabs. The Turkish Navy is larger certainly, but not overwhelmingly so, especially when considering the quality and capabilities of the ships. So it would come down as so often, to the troops, sailors, junior commanders, field commanders and the high command. The experience, intelligence, resourcefulness, courage and willpower of the participants would be a determining factor in such a battle over the Black Sea.

But this is not the battle at all that we need to contemplate. Firstly, the above figures misleadingly compare the entire Turkish Navy, to only the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Some sources estimate the Turkish Navy at 300,000 tons displacement. The Russian Navy was a few years back (now larger) estimated at over 1.2 million tons displacement. Additionally, the average ship in the Russian navy is newer and of a higher quality than the average Turkish one. These modern ships with greater electronic capabilities, as well as guided missile armaments, tend to be smaller in displacement (and faster) than older warships. Thus the 12 to 3 ratio hides an even greater Russian advantage.

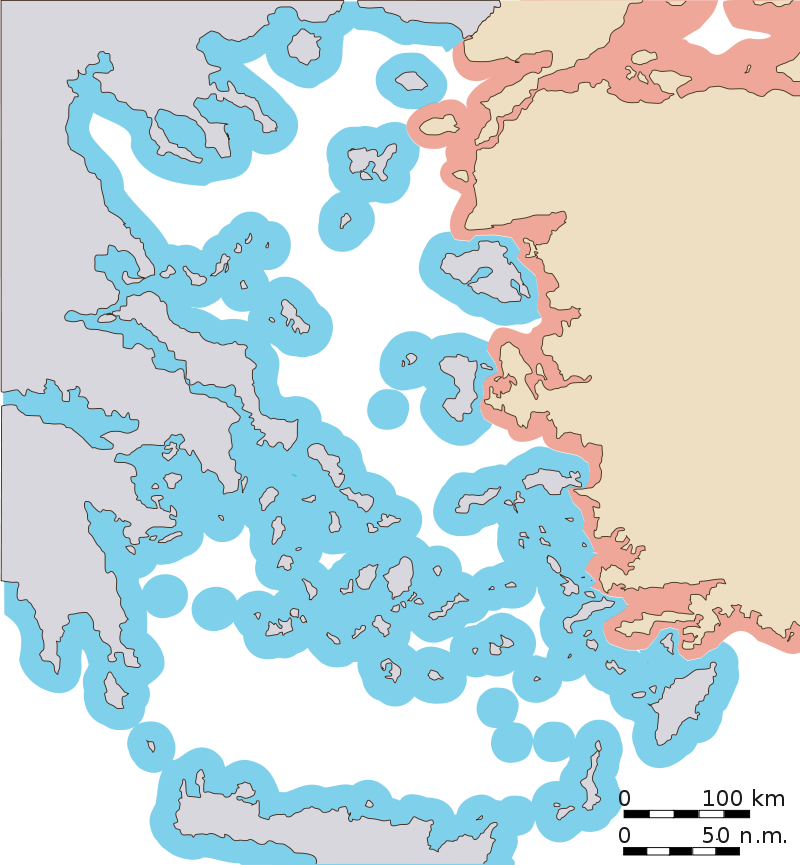

Of course, the entire Russian navy would not and could not face the Turkish navy, but neither would the entire Turkish Navy face the Black Sea Fleet. Turkey’s navy is stretched thin as it is, with its interests and aspirations in the eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Cyprus and the Aegean Sea. Turkey is surrounded by “non friends” if not outright enemies in the region, and has significant current and historical conflicts in the eastern Mediterranean with Greece, Cyprus and other regional players. Turkey would not be willing to dedicate, not to mention risk, its entire navy to battle in the Black Sea. The Turkish coastline is 8,333 km long with a myriad of islands and inlets, with plenty of international disputes, especially in the Aegean and in cypress. These include delimitation of territorial waters, airspace, exclusive economic zones and even some small islands. Turkey cannot afford or would not want to stop patrolling its borders and defending these disputed interests.

Furthermore, while the large Russian navy is limited in its current deployment in the Black Sea, nothing would stop it from arriving in larger force into the eastern Mediterranean. The other Russian fleets have access into the Mediterranean through the strait of Gibraltar and the Suez canal.

Turkey deciding to take on the Russian Black Sea Fleet would be open to face much of the rest of the Russian Navy in the Mediterranean.

More important than all of the above, the battle for the Black Sea hardly would need to involve the Black Sea Fleet, at least not endangering its capital ships near Turkish ones. The battle would be largely an air and air-to-sea battle. Drones (air and sea-going), missiles, and traditional air forces on the one hand, with jammers, radars, and anti-air defense systems on the other would largely determine the outcome.

Russia’s air force dwarves the Turkish one by any measure. It’s AD integrated capabilities likewise completely outclass the Turkish ones, especially after over a year of hard fighting, testing, learning and improvements. The dedicated Black Sea air assets in such a situation would be complimented by any number of assets from the rest of the Russian air force, and would be more than enough to deal with any naval and/or aerial incursion by Turkish forces northwards into the Black Sea. The Black Sea Fleet itself is almost unnecessary in this regard.

Finally, aside from actual naval and aerial combat in the Black Sea and/or the Mediterranean, Russia is capable of stirring up a lot of additional trouble for Turkey in any confrontation which the struggling state can hardly afford. Russia can support Kurdish forces, both within Turkey and along its borders. It can support its Syrian allies to attack Turkish interests within Syria and beyond. It can encourage and help Iran to do the same, both within Syria and along their shared and tumultuous border. Russia can change policies and support Armenia against both Turkey and Azerbaijan to a much greater degree.

It could decide to bomb Turkey itself with its proven long range capabilities. A weakened Turkey, is likely to be set upon by its regional enemies, internal and external, Greece and Cyprus among them but not alone. Everyone in the region from certain Libyan factions to Egypt and of course Israel have disputes with Turkey’s growing assertions in the eastern Mediterranean. A direct conflict with Russia is likely to do little for Turkey other than prove its military weakness, and encourage its rivals and enemies to act against it.

On first thought, one may think that Russia, stretched to the limit as it is, could not possibly afford a war with Turkey. But the reality is that conflicts can take many shapes and forms. Russia and Turkey share no land border. A conflict between them would be limited (in the direct fashion) to naval and air forces. Russia has these to spare as they can only be used in the SMO on a limited basis.

However, they have gotten a chance to fight, coordinate with each other and other forces and learn modern warfare for over a year. The initial clash with the rusty and demoralized Turkish Navy would be likely to leave her stunned, along with most world observers.

In conclusion, as if all of the above was not enough, we need to add an additional parameter that would favor Russia in such a conflict. The conflict need not even be; not in a total sense nor in the limited scope described above.

The burden is on Turkey if it wants to break the Russian blockade. While wishing to resist going into the weeds, and a deep dive into the military scenario we envision here, and already having described it at more length than it was necessary, this final parameter is well worth a brief description.

We have seen a lot of what a near-peer modern war can look like. And though we have seen more of ground combat (or at least a type of it, with a great deal of artillery), we have seen plenty of air and naval action as well. Already during WWII in the Pacific, battleships were quickly proving obsolete, and air forces (largely launched from carriers) were the deciding factor in naval combat.

We have seen in this war a massive intensification of aerial and anti-air capabilities due to improvement optics and guided missile technology. Nothing large can fly over enemy airspace without great peril, and nothing can move on the ground without easily being spotted from above. Spotted and thereafter so often neutralized by air to ground munitions' of all types.

That is on ground. In the water it is even more so the case. We saw the Moskova sunk. We saw Russia’s inability to hold snake island close to the Ukrainian coast. Ukraine’s navy to speak of is gone, but it has been operating plenty of drones (air and sea) and missiles over the Black Sea and even used them ins significant attacks against Crimea. Russia’s navy rules the waves in the small sea, but it cannot get near to the Ukrainian coast. Ukrainian drones, artillery systems, and air-to-ground/sea and ground-to-sea missiles quickly could overwhelm any ship that ventures even relatively near (and far from its own AD protected coast). If it gets really close to the coast, it would also fall prey to anti-ship missiles launched from coastal positions.

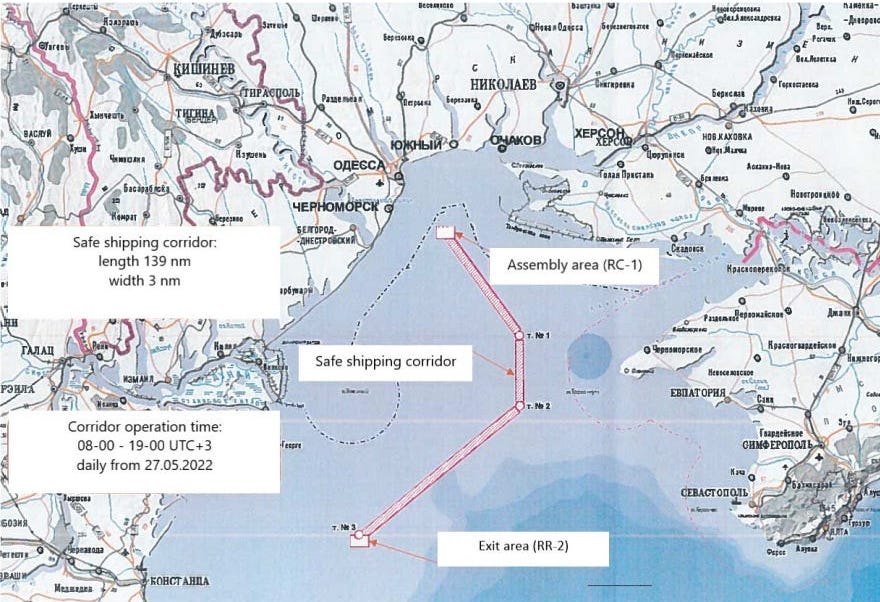

With this in mind, as we described more fully in earlier articles (including the one quoted above) about the Grain Deal and the blockade, Russia need only control the northern Black Sea; the approaches to the Odessa ports.

With everything we have considered, to imagine the Turkish Navy pushing north all the way to Odessa escorting (brave) civilian grain ships into and out of the port stretches the imagination. The outdated and inexperienced Turkish ships, far from their home ports, their air force and most importantly their AD systems, would be easy prey to Russian strikes as they moved into the exclusion zone.

This is so apparent to anyone that actually tackles the problem, that Turkey knew very well it cannot even attempt to do this. The headlines told us that Turkey called Russia’s bluff, but at least in this round it was the other way around.

Even if Turkey something pulled that off, or at least attempted it, civilian ships are not audacious buccaneers of the seven seas. They, in general, will not go into a war zone, into a MEZ (as we discussed previously), and cannot get insurance to do so. Commodities prices for grain do not warrant nor allow such margins of courage. All this without even considering that the once again the economics of efficient commodities trading, do not include destroyed ports. The port facilities themselves, especially around Odessa, Izmail and Reni, will become (and have already become as we have seen) targets. Docks, dry-bulk facilities, and warehouses alike.

The ships themselves would have to be manned by Ukrainian navy sailors for example, and either be uninsured or state insured (buy Ukraine with western support). To man them with UA troops would only make them a tastier target for Russia. Slow, large dry-bulk carriers are not the kind of vessels that can survive the Russian Armed Forces, with or without a Turkish escort.

So what was Russia’s Problem?

So if this all so evident, why did it seem like Turkey could really bully Putin around?

Well, much of this was discussed in previous pieces and I won’t rehash it here. But sufficed to say, that Russia did not fear fighting a couple of old Turkish Frigates sailing north escorting a theoretically brave grain ship towards Odessa.

There are two more serious problems.

Turkey like it or not, is a NATO country. How could Russia fight with her in any fashion?

Turkey, even if it cannot control the Black Sea, controls the Bosporus straits.

Turkey’s leverage lied more along these lines, along with other geopolitical realities. Let us address these two briefly. If Turkish ships pressed northwards into the Black Sea, and violated Russia’s Maritime Exclusion Zone, and were therefore attacked by Russia within the MEZ, this would in no way activate Article 5 of NATO.

The ships, far from Turkish territorial waters, and within an MEZ now declared and respected for over a year, would be fair game. NATO undoubtedly also informed Turkey of this fact. More likely, this worked in the opposite. Because Turkey is a NATO country, the other members would exert great pressure on it not to embark on such adventurism on its own; and if it did, it would go it alone.

Now for the straits. True, the most direct and easiest leverage Turkey could have over Russia is simply to close off the straits to her, and for good measure allow anyone else who wants to come into the fray in. For example, let the US 6th Fleet intot the Black Sea. Let all other Navies hostile to Russia into the sea as well. Meanwhile, Turkey could not only block any Russian naval vessel from entering or exiting the Black Sea but also cut off all trade to Russia. It could simply block of access to any ship coming from or going to Russia.

That is the true physical leverage that Turkey potentially has over Russia. However, it is a power Turkey would be very weary to wield, and one which legally it could do so (and very arguably at that) if it was in a state of war with Russia. The previously mentioned Montreux Convention does not allow this.

Turkey’s unquestioned control of the Bosphorus strait is based largely on honoring the Montreux Convention. All nations have a free right of passage through the strait and free at that. Warships also normally have free passage, especially those from Black Sea nations (while non Black Sea states have some limitations expressed in the treaty). During war, Turkey may or must block passage by warships of any warring party (ie Ukraine, Russia, and arguably the western donor nations), which it has done. Only ships normally registered to the Black Sea ports, such as those of the Black Sea Fleet may transit back home during war.

Breaking the Montreaux, honored for nearly 100 years, and itself a convention of other more ancient treaties, would not go over well for many states, especially the Black Sea States themselves: Bulgaria, Romania and Georgia besides Russia and Ukraine. It also would not go over well with the majority of states that simply wish to maintain freedom of navigation for commerce, and regional stability.

Even hardcore Ukrainian supporters in the Western NATO countries might actually think twice at supporting a break in the convention. Once Turkey is allowed to unilaterally break the convention without consequence, it becomes of little worth, and there is nothing to stop her from doing so in the future. Commerce across the strait is vital for the European, Mediterranean and ultimately world markets.

Blocking ships going to and from Russia would also entail blocking ships of any number of neutral or friendly (to Turkey) states. Most ships visiting Russia’s ports do not do so under a Russian flag. Turkey would be hard pressed to justify blocking ships from a myriad of countries from their transit rights under the long honored convention.

At the very least, this would cause a slew of sanctions and embargos in retaliation towards Turkey. For Turkey’s part additionally, just like breaking of the convention erodes its value to the world community, Turkey could no longer count on their support for continued rule over the vital straits. This is especially problematic for a NATO country (that wishes to remain in NATO) and an aspiring (and in some ways de facto) member of the EU.

In short (or very long), the juice is not worth the squeeze. Turkey, at least certainly not alone nor unilaterally, would be very foolish to try to run the Russian gauntlet in the black sea.

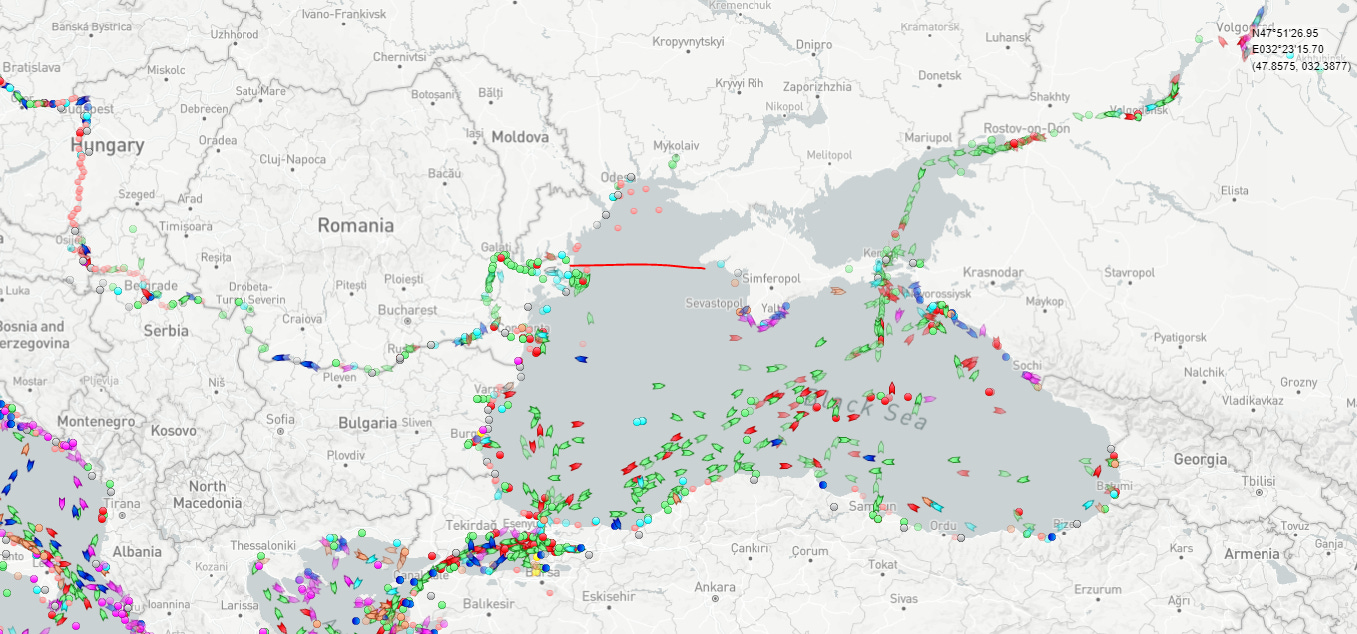

As of writing, you may see that naval traffic is strictly obeying the Russian MEZ and not venturing north of the Romanian - Ukrainian border (where the Danube empties into the Black Sea). Meanwhile, there is plenty of traffic to and from Russian ports.

Likewise we see that there is a large backlog of ships at the mouth of the river.

Ukraine can continue to export and import, grains along with everything else, either by rail and road westwards mostly towards Poland, or by sea using the river ports of the Danube.

Traffic can actually either flow westwards and later northwards along the Danube to Europe or to Romanian ports for transit out of the Black Sea out of Constanta for example. Once a ship has left a Romanian or Bulgarian port, it can travel freely and Russia will not disturb it. The logistics of getting bulky commodities to these ports is very difficult for Ukraine. And simply sailing close to the shore southwards until you are out of the MEZ or in Romanian waters is not really an option for most civilian carriers, who would still be in great danger.

Ukraine really needs to get goods in and out of Izmail and Reni on the Danube to be able to have outside access. These ports already have become targets recently as the Battle for the Black Sea Begins.

This is not a battle between Turkey and Russia, like many expected, but between Ukraine, western backed, and Russia. Ukraine will try, largely with unmanned aerial and naval vehicles to damage and destroy the Black Sea Fleet, to cut off the Crimean peninsula by hitting the bridges, and to protect a certain part of the Black Sea, nearer its shores, to allow maritime trade.

Russia for its part, will try to enforce its MEZ and destroy the port facilities of Ukraine so that any trade is untenable. This way, Russia hopes that while trade may resume by another round of Grain Deal extensions (or its descendent treaty), it will not happen without its cooperation.

Grain economics

As a last note, we should take heed that exporting bulky and cheap (per volume) commodities such as grain will not be easy for Ukraine using the river ports, even before being under fire.

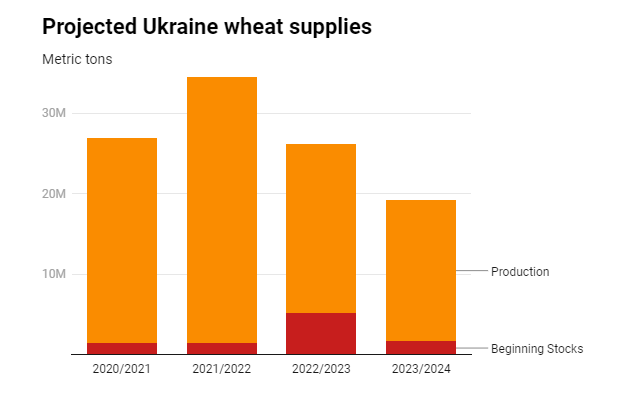

Grain exports had already been dropping as Russia lowered its cooperation under the deal. They went from a peak of 4.2 million metric tons in October to just over 2 million tons in June. And though the Grain Deal ended officially at or around July 15, the last ship under its protection left by June 29. Thus we can expect the July figures to be much smaller.

For comparison, loading 70,000 tons of grain though the port of Yuzhne (one of the main Odesa area ports) would take around 3 days and fit on one Panamax vessel. Yuzhne it should be noted is also much closer to the agricultural sources of the grain, than the extreme southwest end of Ukraine where these small Danube river ports are located. As it is, it is an area connected delicately with the rest of Ukraine by the Pidyomnyy Mist (long termed “the most hated bridge in the world” by DPA’s Wyatt), which is a favorite target for Russian missile strikes.

To load these same 70 thousand tons through the Danube ports, you need 10 to 15 coaster ships and 15 to 25 days. The Danube allows ships only of 7,000 tons compared to ships of up to 140,000 tons that Yuzhnyi allows. That is a 20x difference.

The Danube is also not large enough for standard container ships, which are useful for the vast majority of items imported and exported. Finally, some recent data indicates that even under the Black Sea Grain Initiative (the Grain Deal), one could expect 7-13 dollars per ton additional cost for the Joint coordination Centre, 4-7 additional dollars for war risk insurance, and another 3-5 dollars freight premium per ton (not many companies were willing or able to deal with the logistics and legalities involved). When talking about a product worth a total of about $150 to $200 per metric ton, these are not insignificant at all.

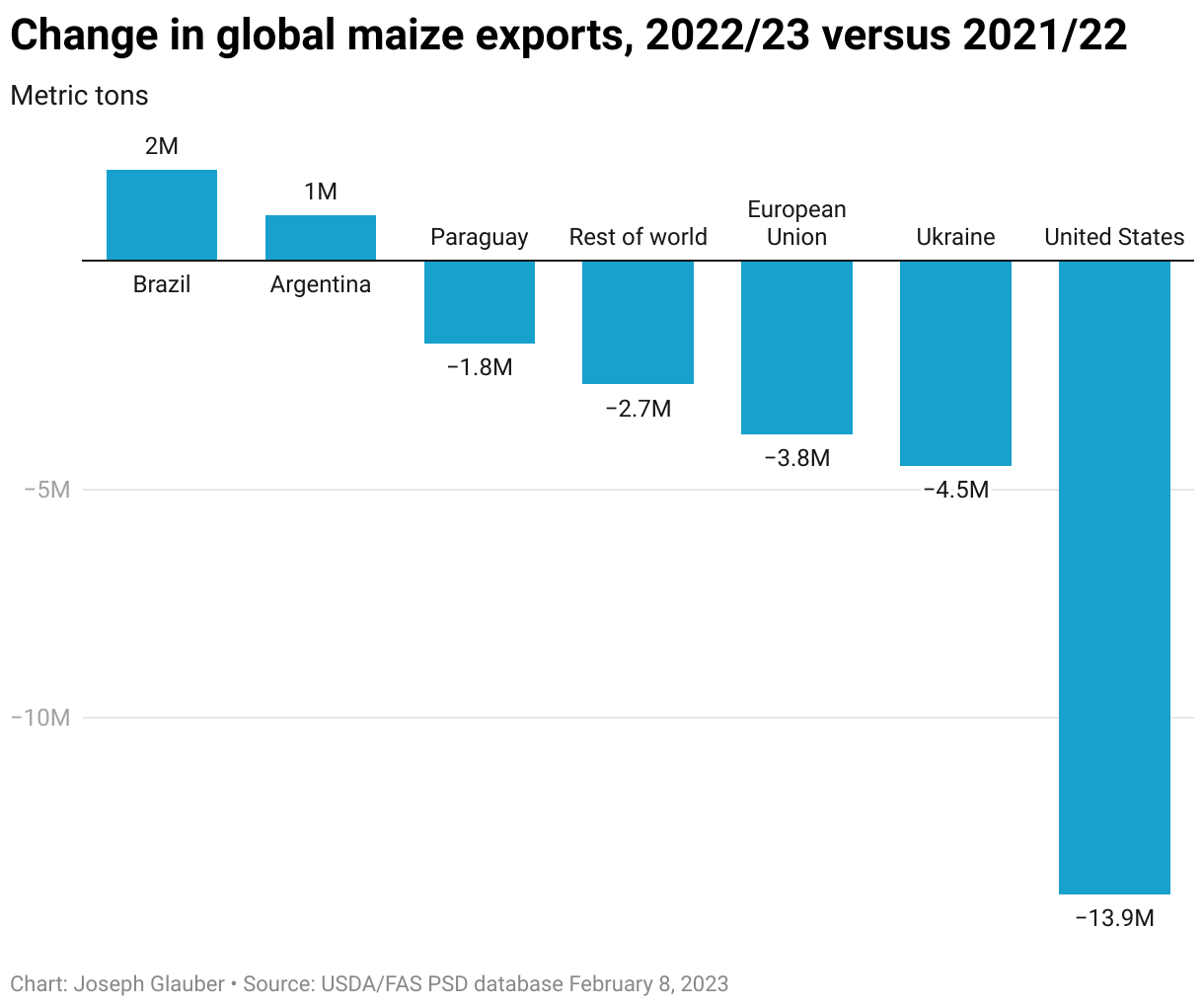

They are dwarfed however, by the costs involved in trying to export out of the Danube river ports, even without taking into consideration blown bridges and destroyed ports. The markets may have thus far underestimated the effect of the lapsed Grain Deal. Sunflower, rapeseed and wheat markets especially will begin to feel the lack of supply from the many expected ships that never sailed out in June, and now much less that have done so in July.

For Ukraine, all of these effects will be exasperated by its neighbors, driven by domestic pressure, have banned Ukrainian grain (due to the market glut and cheap prices).

Ukraine is finding paying for its massive mobilization and the war in general ever more difficult. Last year it devalued the hryvna, so that Zelensky’s promised large salary for all soldiers dropped significantly (in USD or real terms). Now, desperate to not devalue the currency again and facing a monthly deficit in the billions, Zelensky went back on his promise and dropped soldier’s pay. The pay scale was based on risk level and complexity of combat roles. The backlash was as expected very dramatic and the government has now gone back and forth in a confusing set of announcements regarding soldier’s pay.

The export of grains was extremely important for Ukraine’s budget, even more so than during previous peacetime years due to the increased percentage of the economy it represents. Under the grain deal about 33 million tons were exported. Even at a low 150 dollars a metric ton, that equals 4,950,000,000 or nearly 5 billion dollars in foreign reserves going into Ukraine and its productive farmers.

Back in 2021 (for the 2021-2022 market year) Ukraine exported the following:

Sunflower oil: $6.4 billion USD (1st in the world)

Corn: $5.9 billion, 19 million metric tons.

Wheat $5.1 billion, 23 million tons

Rapeseed: $1.7 billion, 2.7 million tons

Barley: $1.3 billion, 5.8 million tons

Total Agricultural Exports: $27 billion USD, accounting for 41% of the country’s overall exports.

Reaching even a fraction of these numbers are crucial for the state’s ability to sustain the war. They not only bring in much needed foreign reserves, needed for critical imports, but are part of the patrimony for a significant percentage of the productive population all along the production, processing, storage and transportation chain. People who otherwise, also fall as an additional burden to the state (or leave the country). For these reasons and more, it was unwise for Russia to allow this advantage for so long to a determined enemy her soldiers were facing in the field in a tough and grueling war.

In any event, of course export will not fall to zero, but the increased cost terrestrial or river export combined with the lower capacity (and lower production) will bring the net sales after the added transportation, storage and logistics costs significantly towards that zero level.

Pre-war shipping volumes for Ukraine were of course much larger. Shipping through the alternate and higher cost “solidarity lanes” (truck, rail, barges) has picked up even as the Grain Deal got going.

For the 2022/2023 season, there was a large supply of beginning stocks due to the large 2021/2022 harvest which was not able to be fully shipped due to the start of the war. Now, there are little beginning stocks, and production is way down due to disruptions related to the war. Ukraine may have much less to export, even if it could access the sea lanes.

Ultimately, the hryvnia is likely to be devalued again and the Grain Deal will no longer support the sustainability of the war dragging on (from Ukraine’s perspective). It is either an increased burden on the west (both in higher food prices and in a larger Ukrainian monthly deficit) and/or an increasing factor in pressuring Ukraine to the negotiating table.

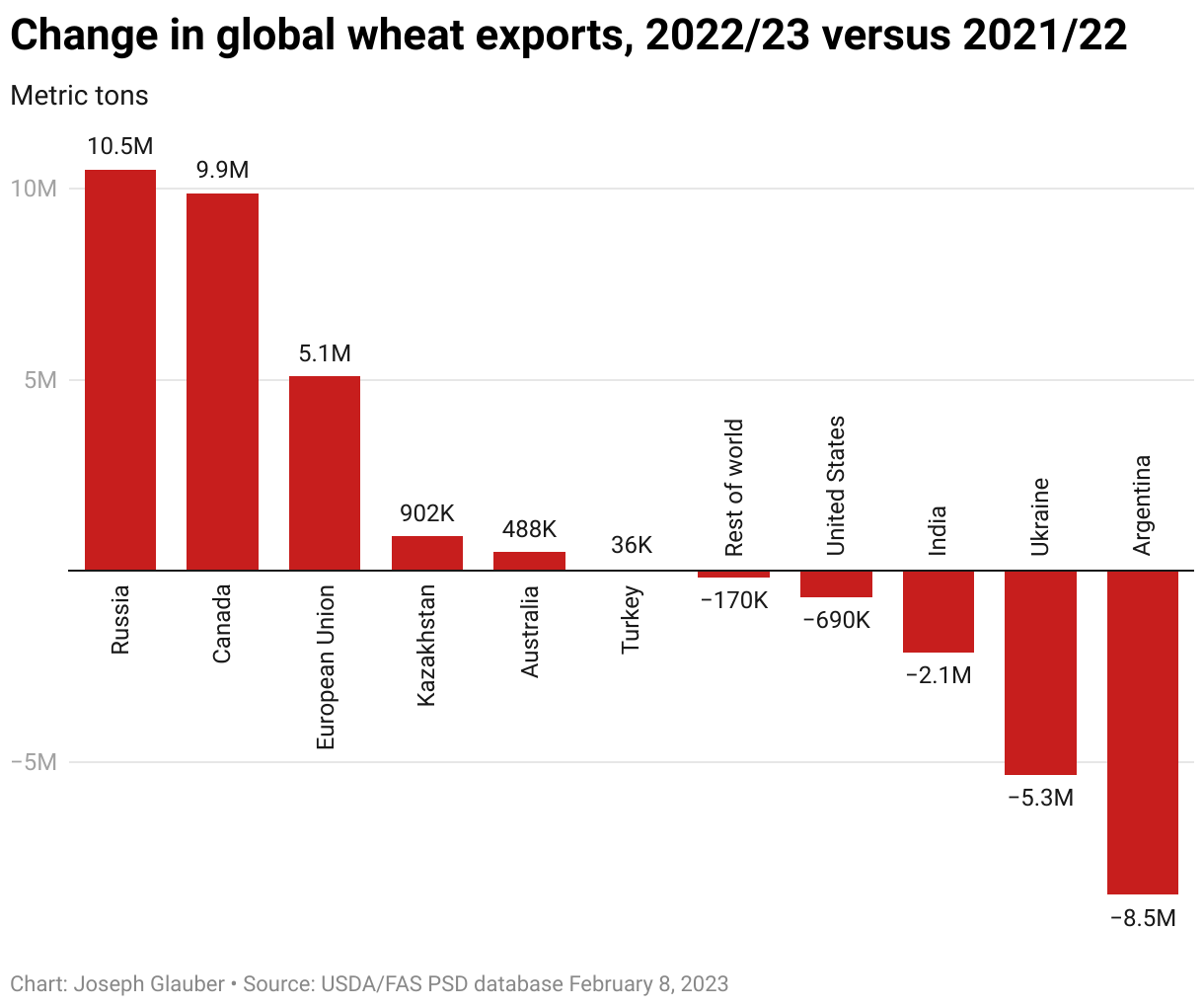

Russia meanwhile, is exporting a record level of grain and even an increase in its market share in the fertilizer trade.

The Grain Deal has ended, and the Battle for the Black has begun. It is a battle, that like the rest of this war, will be fought by Russia and Ukraine, the world looking on in fear, admiration and horror; Turkey’s Erdogan stood in the limelight for a moment, while the two Slavic nations clobbered each other, but his bluff called he has been brushed aside, and the gladiators, wrong or right, still have much fight left in them.